“Wellness design” now has a different meaning. Not long ago, architects were talking about design that encouraged building occupants to use the stairs more often. Now, we’re talking about survival.

In a May 19th presentation to the Housing Council of the Urban Land Institute’s New York chapter, Jessica Katz – Executive Director of the Citizens Housing and Planning Council (CHPC) – argued for a return to a public health perspective on urban housing. As important as it remains to increase the quantity of housing in our cities, we need to balance it with a focus on the quality of that housing and on the public policy mechanisms by which it is provided.

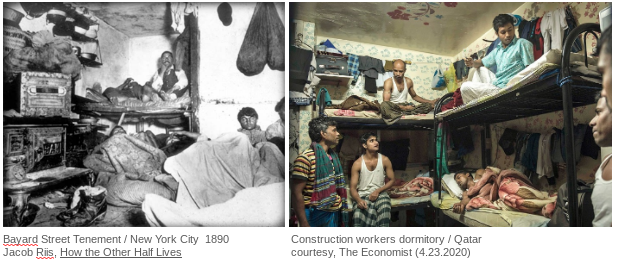

When Jacob Riis first published How the Other Half Lives in 1890, it cast a spotlight on the connection between overcrowding and social well-being. The same lesson is being re-learned today in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic as we see infection rates spike among migrant construction workers in Asia and the Middle East and in poor and working-class urban neighborhoods where residents are less able to socially-distance themselves from their families, roommates, and neighbors in dense surroundings. For example, “Singapore has seen a surge of coronavirus cases among migrant workers after months of successfully controlling the outbreak … corona-virus cases linked to migrant worker dormitories accounted for 88 percent of Singapore’s 14,446 cases, including more than 1,400 new cases in a single day.”1

Even before the pandemic, architects in the Middle East were being asked to help address the oppressive conditions foreign laborers were being subjected to. Their situation is now more urgent than ever.

Just over 100 years ago, New York City adopted the world’s first city-wide zoning ordinance, largely to address public health and safety. “The time has come when effort should be made to regulate the height, size and arrangement of buildings,” George McAneny, the borough president of Manhattan, declared in 1913 “to arrest the seriously increasing evil of the shutting off of light and air from other buildings and from the public streets, to prevent unwholesome and dangerous congestion both in living conditions and in street and transit traffic, and to reduce the hazards of fire and peril to life.” The consequences of the new zoning law were significant and lasting. “The reduction of density in Manhattan is directly a product of the 1916 Zoning Resolution,” (former planning commission chair Carl) Weisbrod said. The 1910 population of Manhattan was 2,331,542, or 164 people per acre. In 2010, the population was 1,585,873, or 109 people per acre”2.

Faced with multiple threats to the commonweal– public health, climate change, homelessness, and a serious affordability gap – the planning community needs to re-double its efforts to bring creative thinking to bear on the challenges facing cities today and the regulatory regime we use to address them.

To that end, some of the proposals set forth by Ms. Katz and the CHPC include:

Affordable Proximity

Essential workers need to be able to afford apartments closer to their places of work, allowing them to be less reliant on public transportation when subways and buses have become scary vessels of potential contagion. Creating a more diverse housing economy will require fresh approaches to development economics, regulations and approvals. For example, CHPC calls for a reboot of our approach to affordable housing lotteries, abandoning random selection in favor of needs-based prioritization.

Management & Maintenance

Building managers have a large role to play in establishing best practices for hygiene and the common use of amenities and social spaces. NYCHA (the New York City Housing Authority), already severely challenged on this front, has an especially critical role to play in protecting the city’s poor and working-class residents.

As the summer heats up, air conditioners and hvac systems will become critical infrastructure if limits remain on city-dwellers’ ability to cool off at pools, parks, and beaches. CHPC calls for distribution of window units to those without them and for ConEd to insure the capacity of the electric grid to handle the increased demand.

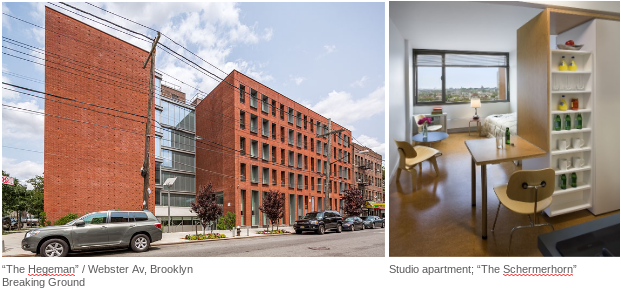

Density

There is no simple one-size-fits-all equation correlating density and virus outbreaks. Some dense places, like Seoul, have leveraged their social infrastructure to effectively contain the virus while some rural areas have seen large outbreaks – as in those around some U.S. meat-packing plants. Ironically, a public health approach to housing may actually call for more density; i.e., more widespread adoption of micro-units where individuals can more effectively and affordably shelter in place. NYC’s pilot program, dating to the 2017 construction of Carmel Place in Kips Bay, seems to have lost momentum of late. Conversely, the success of supportive housing projects like Breaking Ground’s “Schermerhorn” and “Hegeman” sites in Brooklyn demonstrate how economic stability and public health can work hand-in-hand in buildings where each resident lives in their own small studio and social services are available on-site to address mental illness, substance dependency and job readiness. Breaking Ground’s data shows that one mentally-ill individual can be housed for $24,190/year (2011 figures) in one of their buildings vs. a cost of $56,530 for the same person navigating the City’s shelter/mental health/criminal justice system3. Especially now, we can clearly see the holistic costs of a large homeless population that is itself vulnerable and in turn poses a threat to the health of others.

For more details on CHPC’s proposals, please visit their website: https://chpcny.org/covidpolicysolutions/

Are cities dead (again)?

Many prognosticators are currently busy prophesying the decline of city-living (once again) in the belief that many current urbanites are anxious to flee dense infected metro areas for the greener (and cleaner?) pastures of suburbia and beyond. And while that may be true to an extent – particularly in the short term – there are a lot of reasons to believe in the continued vitality of urban living in the long run. As we saw in the aftermath of 9/11, short-term fears can be overcome by the gravitational pull of a city’s economic, social, and cultural strengths.

In time, public attention will shift from our current fast-moving health crisis to the slow-moving crisis of climate change. In that fight, dense transit-oriented living remains a potent tool for combating global warming and environmental degradation. Some potential outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic could play a part in reinforcing those strategies. For example: if, as many people believe, Work-From-Home becomes a larger part of the permanent employment landscape, one can reasonably imagine a demand for walkable communities, close to home, that possess many of the hallmarks that have made city-living historically attractive: convenient restaurants and retail, availability of local professional services (doctors, lawyers, etc.), cultural opportunities (galleries, theaters, etc.) and great public open spaces (plazas & parks). After our current lockdown experience, who among us would want to be permanently stuck at home with no relief from our own four walls? Less commuting would certainly help lock in some of the improvement in air quality that we’ve seen while in shut-down mode.

Archilier Architecture’s 2019 masterplan for a 100-acre mixed-use community in Santa Ana, California offers a model for healthy neighborhoods in our post-pandemic landscape. “Santa Ana Gardens” — adjacent to a future light-rail line link to the city’s downtown commuter rail station — provides 2.3 million square feet of residential space in a variety of configurations to meet the needs of singles, families, and seniors. Over half-a-million square feet of retail and professional office space comprise a commercial village within a fifteen-minute walk of every dwelling. A hotel in the village offers meeting space for local businesses and events while light-industrial loft space is provided along the rail line for artists, artisans, and ‘makers’ to ply their craft. The street layout is designed with a comprehensive network of bicycle paths and there is over ten acres of parks and plazas for both passive and active recreation.

Healthy living will remain more than just the ability to isolate from your neighbors when necessary. Whether in cities, small towns, or suburbs, we still need to encourage lifestyles that balance the desire for personal health & safety with the need to live sustainably together on our planet. Archilier Architecture plans to remain on the frontlines of charting a healthy, sustainable future for our species in the face of whatever challenges the future may hold.

- 1NY Times 4.28.2020

- 2NY Times 7.25.2016

- 3breakingground.org